Film Spotlight

Quartet for the End

directed by Gregg Biermann, US, 13:33

An end is not a fixed moment that exists only when everything is completed, finished, or gone. An ending is a process, one that takes enough time that it can be recognized, perhaps too late, for its unstoppable progress toward conclusion. Gregg Biermann’s Quartet for the End (2023) comments on what it means to face the end. The film can be seen as a parable for humanity’s greatest threat, failure, and incipient disaster— manmade climate change— one that throws us into a chaotic cycle of dread and deja vu, comforted only by the same nihilistic delirium that prompts a string quartet to play on as the Titanic sinks.

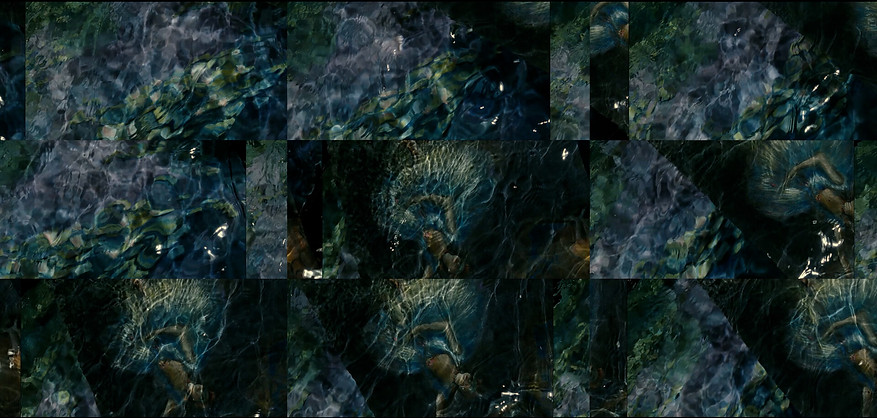

As in other films by Biermann, Quartet for the End explores the movements and rhythms of its source text, in this case one of the climactic sequences of James Cameron’s Titanic. The frame is split into an imperfect and slightly changing grid, with each smaller rectangle playing the same short excerpt, off-set by a few frames or a few seconds. The result is kaleidoscopic; when the frame is dominated by repetitions of the same closeup, we see minute movements amplified by the simultaneous display of several different moments of each gesture. Even when the structure of the piece makes itself clear, slight variations appear. This leaves the viewer dizzied not only by the tossing and turning chaos on the sinking ocean liner but also by the ever-shifting frame edges that slide laterally like the objects falling off the mantle of a first-class room. The soft, mournful tones of the quartet itself, played to comfort the passengers fighting for their lives, is overshadowed by shouts and impacts, crashes and collisions, which in turn repeat in their own rhythm dictated by the film itself. As a result, any solemnity is replaced by abject horror as we see people take the same futile actions over and over, we see others repeatedly resign themselves to death, and we see the musicians themselves continuously, and perhaps pointlessly, focus on their playing.

Quartet for the End’s interrogation of the Titanic sequence is temporal and graphic, as we see new lines and shapes appear and disappear through the combination of similar but off-set frames. Just as the people on the Titanic are desperate and trapped, so too is the viewer, only without the hope of a seat on a life raft. We can take some solace in the comfort of our seat in the theater, though this comfort is spoiled by the realization that the repetitive inevitability of sea levels rising to lethal heights is one we share with the characters on screen, and a problem we have equally little power to curtail.

In his description of the film, Biermann refers to the hypnotic waves of repetition as “a reverberating contrapuntal web,” which are vexingly beautiful. It is a beauty that stings, built on the images of chaos, destruction, grief, and death. Taken as a post-hoc justification for tragedy, the beauty is repulsive. Taken as proof of the viewer’s ability to be distracted from empathy by aesthetics, the beauty is loathsome. Taken as evidence of the naiveté of our stupid optimism that looks for a silver lining even in the storm clouds of the Apocalypse, the beauty is an indictment. But in the end, beauty is beauty. The viewer must reckon these conflicts alone before the boat sinks. The clock is ticking.

To complicate the viewer’s position even further, Quartet for the End jumbles two spectacles together: the sinking of the Titanic and the climax of Titanic. The quartet provides the soundtrack for death both for those on the boat and those in the movie theater. The viewer is flung into the diegesis, thrown off balance by the broken, looping images, deafened by the cacophony of melodic strings and destructive waves, and drowning in the dread of 1912 and 2024 simultaneously. This film’s power flows from the macabre and magnetic fascination with the real-life events themselves, though this fascination is one that is clearly mediated and enhanced by the James Cameron film. The spectacle of the Titanic is uncannily cyclical; a tin whistle siren song that lures the ulta-rich toward its depths while the rest of us watch in amoral, morbid glee. The real-life passengers of the Titanic are as much part of the story as Leonardo di Caprio; to risk your life in a visit is as much reverence to history as it is a pop culture pilgrimage.

Finally, it is worth remembering that this is a period film, too. This is a film that can only exist in the short epoch where there overlapped two phenomena that collide disastrously in its climax. First, transatlantic travel, which is relatively new in human history, a mere blip in the history of the planet. Second, icebergs, which humans have nearly defeated like the buffalo and the bumblebees. As we face the existential doom that follows as a consequence of climate change, Quartet for the End reminds us that whether we are sinking or the waters are rising, the result will be the same. Can we go back in time? Maybe, but only to watch.

-Billy Palumbo, Festival Director, Visiting Associate Professor, OCU Film